(CDC, May 23, 2020):

“Interim Guidelines for COVID-19 Antibody Testing -

Interim Guidelines for COVID-19 Antibody Testing

in Clinical and Public Health Settings”

In the current pandemic, maximizing specificity and thus positive predictive value in a serologic algorithm is preferred in most instances, since the overall prevalence of antibodies in most populations is likely low.

For example, in a population where the prevalence is 5%, a test with 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity will yield a positive predictive value of 49%. In other words, less than half of those testing positive will truly have antibodies. …

… Serologic test results should not be used to make decisions about grouping persons residing in or being admitted to congregate settings, such as schools, dormitories, or correctional facilities.

Serologic test results should not be used to make decisions about returning persons to the workplace.

Until more information is available about the dynamics of IgA detection in serum, testing for IgA antibodies is not recommended.

.

(Smithsonian Magazine, May 26, 2020):

“Why Immunity to the Novel Coronavirus Is So Complicated -

Some immune responses may be enough to make a person impervious to reinfection, but scientists don’t yet know how the human body reacts to this new virus”

… while a positive antibody test (serology test) can say a lot about the past, it may not indicate much about a person’s future. Researchers still don’t know if antibodies that recognize SARS-CoV-2 prevent people from catching the virus a second time - or, if they do, how long that protection might last.

Immunity isn’t binary, but a continuum - and having an immune response, like those that can be measured by antibody tests, doesn’t make a person impervious to disease. “There’s this impression that ‘immunity’ means you’re 100 percent protected, that you’ll never be infected again,” says Rachel Graham, an virologist studying coronaviruses at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health. “But having immunity just means your immune system is responding to something” - not how well it’s poised to guard you from subsequent harm.

It takes a symphony of cells. In discussions of immunity, antibodies often end up hogging the spotlight - but they’re not the only weapons the body wields against invaders. The sheer multitude of molecules at work helps explain why “immunity” is such a slippery concept. …

… Antibodies aren’t perfect. Even the most sensitive laboratory tests have their limits, and finding antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 is no guarantee that those molecules are high-quality defenders or that a person is protected from reinfection. …

… One common misconception is that a positive antibody test means a person no longer has the virus in their system, which isn’t necessarily the case. …

… A person who has recovered from their first brush with a new pathogen like SARS-CoV-2 may travel one of several immunological routes, Goldberg says - not all of which end in complete protection from another infection. …

… not everyone reacts the same way to a given microbe. People can experience varying shades of partial protection in the wake of an infection, Goldberg says. In some cases, a bug might infect a person a second time but struggle to replicate in the body, causing only mild symptoms (or none at all) before it’s purged once more. The person may never notice the germ’s return. Still, even a temporary rendezvous between human and microbe can create a conduit for transmission, allowing the pathogen to hop into another susceptible individual. Under rarer circumstances, patients may experience symptoms that are similar to, or perhaps even more severe, than the first time their body encountered the pathogen. …

… A person’s immunity to a pathogen can wane over the course of months or years, eventually dropping below a threshold that leaves them susceptible to disease once again. Researchers don’t yet know whether that will be the case for SARS-CoV-2. …

… So far, early studies in both humans and animals suggest exposure to SARS-CoV-2 marshals a strong immune response. But until researchers have more clarity, Graham advises continued vigilance - even for those who have gotten positive results from antibody tests, or have other reason to believe they were infected with COVID-19.

.

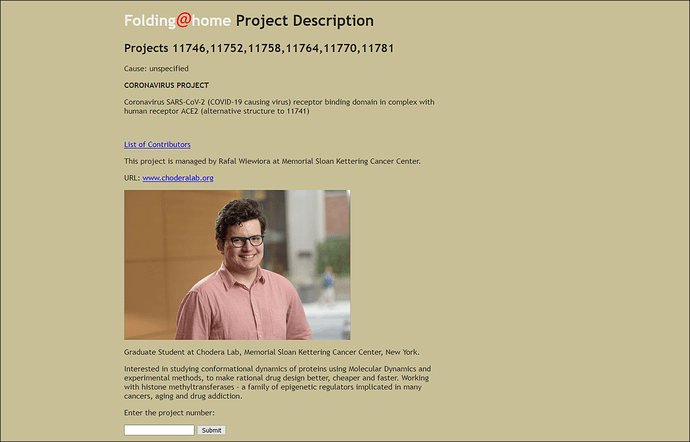

(Rockefeller University, May 22, 2020):

“First results from human COVID-19 immunology study

reveal universally effective antibodies”

The first round of results from an immunological study of 149 people who have recovered from COVID-19 show that although the amount of antibodies they generated varies widely, most individuals had generated at least some that were intrinsically capable of neutralizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Antibodies vary widely in their efficacy. While many may latch on to the virus, only some are truly “neutralizing,” meaning that they actually block the virus from entering the cells. Since April 1, a team of immunologists, medical scientists, and virologists, has been collecting blood samples from volunteers who have recovered from COVID-19. The majority of the samples they have studied showed poor to modest “neutralizing activity,” indicating a weak antibody response. However, a closer look revealed everyone’s immune system is capable of generating effective antibodies - just not necessarily enough of them. Even when neutralizing antibodies were not present in an individual’s serum in large quantities, researchers could find some rare immune cells that make them. …

… “We now know what an effective antibody looks like and we have found similar ones in more than one person,” Robbiani says. “This is important information for people who are designing and testing vaccines. If they see their vaccine can elicit these antibodies, they know they are on the right track.”

The research paper referenced in the above-quoted article:

“Convergent Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Infection

in Convalescent Individuals”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infected millions of people and claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Virus entry into cells depends on the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S). Although there is no vaccine, it is likely that antibodies will be essential for protection. However, little is known about the human antibody response to SARS-CoV-21-5. Here we report on 149 COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Plasmas collected an average of 39 days after the onset of symptoms had variable half-maximal neutralizing titers ranging from undetectable in 33% to below 1:1000 in 79%, while only 1% showed titers >1:5000. Most convalescent plasmas obtained from individuals who recover from COVID-19 do not contain high levels of neutralizing activity. Nevertheless, rare but recurring RBD-specific antibodies with potent antiviral activity were found in all individuals tested, suggesting that a vaccine designed to elicit such antibodies could be broadly effective.